Breaking down and building up climate action

Why mitigation and adaptation go hand in hand — and so must we.

What do you think of when you think about “climate action”?

Really, what do you think about? No wrong answers.

*

protests?

*

solar panels?

*

energy star ratings?

*

keep cups?

*

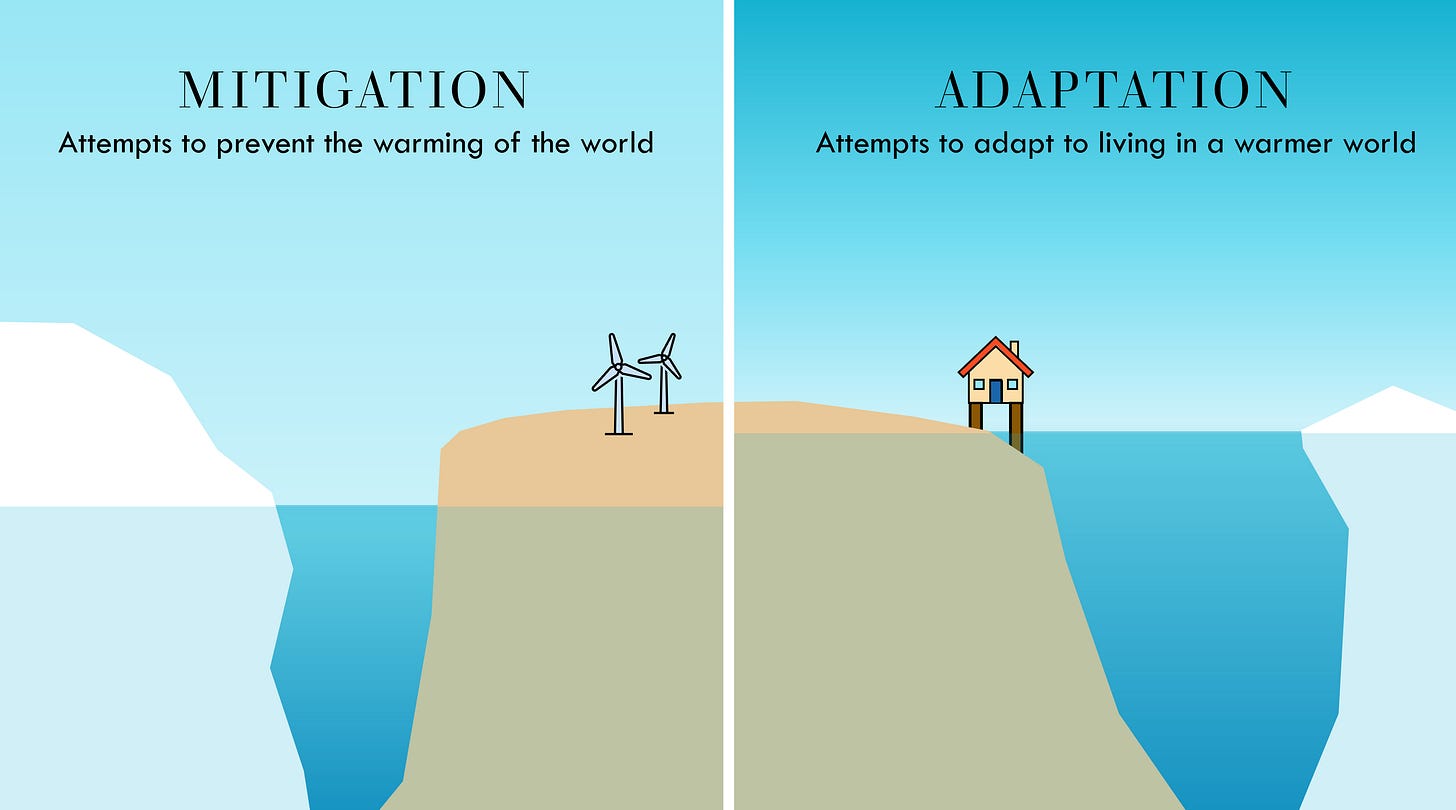

Now, what type of action did you think of? Was it a mitigation strategy or an adaptation strategy? Here’s a quick visual breakdown of the difference:

In brief: a mitigation strategy is a proactive attempt to prevent global warming. Using low-carbon energy sources like electricity from solar or wind rather than fossil fuels is a way of minimising carbon emissions, which in turn reduces the risk of global warming. Activities that reduce waste (recycling, etc.) do this too, by minimising landfill and reducing the amount of new materials being manufactured. And regenerative actions, like reforestation, mitigate warming by absorbing carbon dioxide from the air and offsetting the damage from our emissions.

An adaptation strategy, on the other hand, is reactive: it aims to make life livable in a changed climate. Better insulation in housing does this by protecting people better from extreme temperatures. Adaptation is also behavioural. We will need to rotate our crops differently because an arid climate means our growing regions will be less fertile. Communities will need robust plans and resources for responding to natural disasters like fires and floods, because they will be constant and severe. And, of course, adaptation is economic. The fewer products we buy (because we’re all reusing and recycling), the more companies will need to reconsider their business models and find new, sustainable ways to create value in the world.

We are currently living at a time when most of us have the luxury of focusing on mitigation. Bushfire-prone communities just are the ones out in the sticks. If we’re living in the cities and our home insulation’s poor, we’ll just turn up the heating — which, hopefully, we’ve converted to electric, and even more hopefully, is powered by the solar panels we’ve had installed.

But mitigation and adaptation are both essential to our survival now and forever. Put simply, the weaker our mitigation responses are now, the stronger our adaptation will need to be to avoid extinction. And if we don’t continue to mitigate while we adapt, then future generations will be in the impossible situation of trying to adapt to living on a burning world.

There are quite a few versions of climate future ahead of us, depending on how and how quickly we act. Climate scientists have produced and continue to recalculate a range of possible scenarios for our world based on what we do (here’s a terrific list from the NZ Ministry for the Environment), so the diagram below is a really rough-and-ready attempt to sketch out the relationship between our climate future and our actions now.

Assuming the actions we take are effective ones, the two variables that matter most of all are speed and collaboration in our actions. The faster we act to mitigate, the less extreme climate change will be. And the more we work together, the better we can protect ourselves and each other from the risks ahead.

But if our actions are slow, the best we can hope for is a reactive response to temperatures that are beyond our control. And if we don’t work together, not only will our preventative measures be weaker, but we’re essentially taking an “each man for himself” attitude to adaptation. The richest few will have access to the best protections. The poor won’t just get poorer; they will burn, starve, freeze, drown, sicken and die.

Climate action is a tough thing to think about. It’s tough because we feel so small. It’s tough because so much of it seems so abstract, or so heuristic. And it’s tough because our actions don’t lead to immediate, tangible rewards. There are minor financial savings to be had with some strategies, but increased costs are far more common. We don’t see the CO2 clearing. We just have to hope what we’re doing is making a difference — and that difference won’t be seen for years to come. But of course the reality is that for every dollar we save on mitigation today, we’ll have to spend unknowably more in future years to adapt to the consequences. Rebuilding fire-resistant homes will cost millions more than re-insulating our current ones and swapping out gas appliances.

But if it’s not something the people around us are doing, it’s much, much harder to bring ourselves to do it.

Reflect on the climate mitigation actions you already take in your own life. It’s okay if there aren’t that many yet. My own list is short. My life is compact and my PhD income is small. For others, it’s the complexity and scale of life that makes it hard: kids, debts, commitments, chaos.

For each action you take, consider what made you choose it. Was it supermarket policy? You did the sums and projected the savings? Tim Minchin serenaded you?

So, so much of what we do is a matter of cultural rhythms. It’s about what the social world around us will support.

Is it possible to foster a culture that recognises and celebrates climate actions? How might celebration look? How can we recognise genuine actions with genuine intent?