Care doesn't scale

I’ve been thinking a great deal about the kind of ethics we need in a world of automation.

Recently, I wrote a brief reference post about systems of ethics: duty-based, consequence-based, virtue-based, care-based. I hoped to use it as a stepping stone towards a more complex discussion about ethical thinking in the current polycrisis. But then I got sick.

At first it was a head cold; then it was a flu; then it was a depressive episode. Which happens to me, periodically, and feels baseless and indulgent and petty and is nonetheless… just… what it is.

It seemed as though the episode followed from the flu, but I am pretty sure it’s what caused it. My bodymind has been utterly overwhelmed in recent months, with the GenAI-in-everything conversation, the huge number of new people in my life, the manufactured assessment crisis, the demolition of US democracy, the genocide of the Palestinian people, the personal attacks, the… you get it. It’s… too much.

And I hate to say it, but it proved the point I had been wanting to make: care doesn’t scale.

There is no algorithm that might make care more efficient. To attempt to scale care is to care less — to actively deplete the world of care.

Towards ethics at scale?

Remember that any “algorithm”, however complex, is simply a set of rules for solving a problem. We usually talk about algorithms as computer programs, but they are purer than this: they are mathematical expressions that find form in digital systems. To digitise is to quantify; to quantify is to make scalable.

An ethics built on principles (deontology) can be automated and scaled. Rules can be coded into algorithms in order to mechanise ethical decision-making based on which principles to apply.

An ethics built on consequences (teleological) can be automated, by aggregating mass data to produce predictive analytics calculating and weighting the probabilities of certain consequences to determine optimal actions. These ethics can be automated; these ethics can scale.

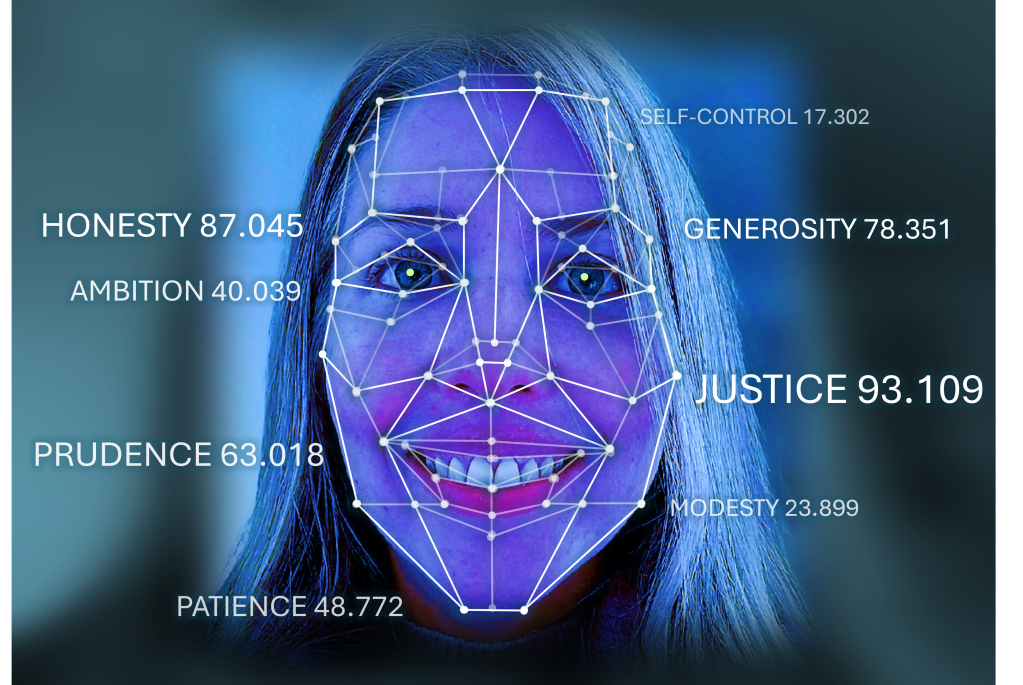

An ethics built on virtue might be more of a challenge to automate, but is again possible by applying data logics. Each of the personal virtues — honesty, compassion, courage —might be profiled through data annotation so that virtue could be mapped in a way not unlike facial recognition, and composite virtue profiles developed to model ethical personae.

But care doesn’t scale.

An ethics of care cannot be automated. There is so much to care about: our families; the people around us; the health of our ecosystems; the work we do, paid and unpaid, to keep our worlds turning. But caring cannot be offloaded. Sure, if we delegate duties to an algorithmic system, the duties remain intact and the system will assign and perhaps even execute them. But if we attempt to delegate care to an algorithmic system, care stops.

The notion of ethics of care has deep roots, but one of its most important thinkers is Nel Noddings, who showed us that care is located in the relation between a person caring about and a person caring for. (Which, of course, can and usually does go both ways.) Caring is, therefore, an intimate relation from which ethical decisions can be made.

But the purpose of automation is to reduce the level of human intervention in forms of activity. The less we have to intervene in an activity, the less we need to attend to caring about it. So we must always remember that every time an algorithm makes something in our lives “easier” or more “efficient”, what it has done is taken care away from the world.

The performance of care might continue. Algorithmic assemblages have become extremely good at saying nice things to make people feel nice. But, as recent cases of LLM-induced child suicide, delusions and murder-suicide have shown us, a chatbot that says nice things is not a chatbot that cares.

But true care is nothing less than a radical rejection of scale. True care is unscalable — because you can’t scale something that is everything.

Feelpunk: to care radically

About a month ago, after we came up with the notion of #thoughtpunk as a principle of algorithmic resistance, a brilliant and deep-hearted friend mused that thoughtpunk was incomplete without #feelpunk. Writing from the perspective of language education, they suggested feelpunk was an idea that combined the rejection of corporate control with:

“empathy, planet focus, decolonial culture and language mediums, and the anti-authoritarianism of inquiry and the pursuit of human connection.”

Anke al-Bataineh

In short, care.

In fact, I think feelpunk is even more profoundly important to algorithmic resistance than thoughtpunk. We must defend our freedom of thought, yes — but it is our ability to feel, to care, which shapes those thoughts. We are in the gravest of danger when the seductive smoothness of the algorithm begins to shape our feelings. This is what Netflix does when it “personalises” a feed of content to manage our feelings and keep us streaming. This is what persona chatbots do before they seduce us into destroying our families’ lives and our own.

So, there are two ways we can lose our care to algorithms: one, to allow them to use our own data to shape our feelings; and the other, to ask them to take our cares away from us by performing them without feeling them. We must never allow either.