Doing postdigital research: What questions can we ask in a world where digital has happened?

I've been searching for a way to conceptualise experiences of engaging in online education alongside adult life. The postdigital feels deeply relevant and opens up potential for further exploration.

I have been searching for a way to conceptualise the complex experience of engaging in online education whilst living an adult life. A concept that feels deeply relevant and opens up potential for further theoretical and methodological exploration is that of the postdigital.

What is “the postdigital”?

“...the post-digital condition is a post-apocalyptic one: the state of affairs after the initial upheaval caused by the computerization and global digital networking of communication, technical infrastructures, markets and geopolitics.”

Cramer, 2015

Definitions of the term are varied. Florian Cramer suggests that “post-digital” can be understood in the same way as “post-apocalyptic”: the event itself (digitalisation) has occurred, and we live in the world that was created as a result. Jeremy Knox writes that “the postdigital might be understood as no longer viewing the digital as ‘other’ to everyday life”.

In the 2023 volume of Postdigital Science and Education, a collective of postgraduate students and teachers shared various disparate views on what “postdigital” means, which to my mind are not mutually exclusive:

as a way of making visible the often-unseen relations between human and technology (Sam Finnegan-Dehn)

as a critical view of technology in application, enabling analysis through various theoretical and political lenses (McKenzie Raver)

as a recognition that digital and analogue worlds are interlinked and recursively shape one another (Henrietta Carbonel).

I find Cramer's analogy a helpful way of understanding the word without holding too much data in my working memory and inviting all of the above views and more. If “postdigital” is a descriptor for that which resides in a world where digital has happened, then the potential ways of exploring what this means flow forth easily - particularly, for me, when contextualised to educational spaces in which digital has happened.

Our recent pandemic experience has created a watershed moment in education in which digital happened to all of us, from the keenest tech-savvy teacher to the most resistant traditionalist. I don't think it's particularly controversial to suggest that COVID was education’s digital “apocalypse”. And now we are faced with the world created in its wake.

Mapping and tracing in postdigital research

“...part of the critical thrust of the postdigital is to attempt to decentre the technology of the digital itself, so that its relations to broader frameworks are brought to the fore.”

Knox, 2019

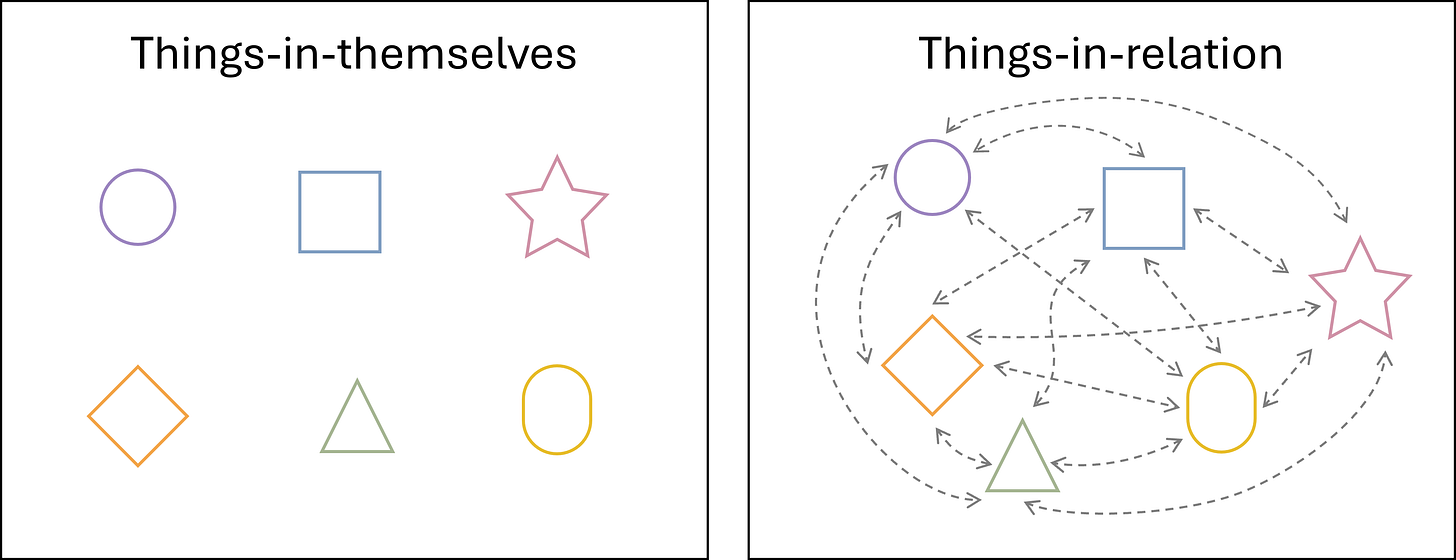

Understanding something as “postdigital” seems to necessitate a sociomaterial view, in which things cannot simply be viewed as things-in-themselves, but are always things-in-relation. The world is different because digital technologies are in it; technologies are different because of how they are in the world. So to take a postdigital approach to inquiry, we must research relations.

Vital to the sociomaterial view is the understanding that there are no separable “things”. To sever them from their relations is to destroy what they are. That is: entanglement is an essential property of thingness.

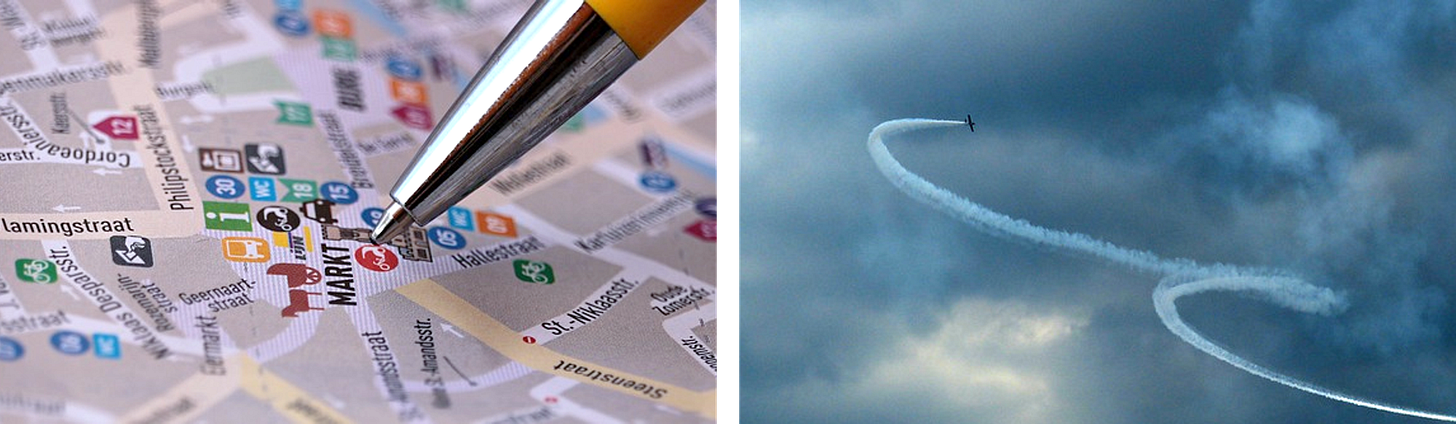

Fawns et al. propose an approach to exploring postdigital interactions through Deleuze and Guattari's notions of “mapping” and “tracing”. These two process metaphors are put forward as methods of illuminating the relations across and between digital, physical and social. Tracing is simple representation; it involves outlining the contours of an already-established configuration. Mapping, however, is a generative process of scoping territories and charting dimensions, enabling speculation about what relations might be possible within them. The map shows where roads could go, while traces show where we've been told they are.

Martin and Kamberelis argue that, unlike tracing, mapping has “political teeth” as it makes visible the power structures and forces that are and might be. But neither exercise is worth much without the other. Maps can be redrawn and the roads rerouted, but without understanding the actual dynamics at play, such revisions are made naively. Traces can reflect what we see before us, but seeing what is already there can obscure what could be - or why.

Ingredients of postdigital research

Fawns et al. propose some principles and attributes of postdigital research. Their co-authored article (mentioned earlier) shows a gentle determination to present any false consensus. Its principles are driven by the same value of richness through diversity. They are valuable to lay over my own initial thoughts about my study's methodology.

I'll conclude with a summary of each proposed principle, along with my reflections about how they might apply to my own future work.

On-yet-around

The authors propose that postdigital research should have a moveable focus which is able to appreciate both the specific object of study (“on”) and its broader, complex context (“around”). This means a study of adults' digital education should simultaneously focus on the immediate digital locus of the learning, and on the larger ecosystem that adults inhabit, of which the digital learning platform is one visible element. This principle resonates deeply, as my original hunch was that learners' online experiences both shape and are shaped by their broader lives on and offline.

Diverse voices and perspectives

The authors also suggest that openness to diverse experiences and ways of seeing the world are vitally valuable to postdigital research as a disciplinary space. The more diverse voices are heard, the richer our ideas will be about what questions can be asked the postdigital. I suspect this is meant to apply across studies rather than within them, but to me this suggests early studies ought also to seek diverse participants, thus a range of postdigital experiences and perspectives.

I am keen to use a maximum variation sampling approach to explore rather than definitively explain what an adult online learning experience looks like.

Fostering transdisciplinarity

In a similar vein, the authors propose that such research be conducted across multiple research disciplines (different methods, different theoretical frameworks, different research contexts). The tension this creates is not easy to navigate, but can produce a far more constructive total field of inquiry which has greater potential for useful insight and even, perhaps, valued change.

As a baby researcher, I must focus on building capability in one discipline first - but I think what I do need to do is seek out others working with postdigital perspectives and learn to sit with the discomfort (and potentiality) of differences in our worldviews.

Creativity, speculation, composition

The final proposed principle of postdigital research is that it embraces generative and speculative methods. The article offers some terrific examples of generative approaches from journey mapping and mind-mapping to scripting and prototyping. Given my own desire to use narrative as a generative methodology inviting participants to construct their own tangible accounts of online educational value, I'm a pretty big supporter of this one.

It seems to sit somewhat at odds with the previous principle of transdisciplinary inquiry, but I am sure the authors did not mean to suggest all postdigital research should be generative - rather that such methods are a vital thread within that trandisciplinary tapestry.

Sources

Cramer, F. (2015). What is ‘post-digital’?. In Berry, D.M., Dieter, M. (eds). Postdigital Aesthetics. Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137437204_2

Deleuze, G., & Guattari, F. (1987). A thousand plateaus: Capitalism and schizophrenia. University of Minnesota Press.

Fawns, T., Ross, J., Carbonel, H., Noteboom, J., Finnegan-Dehn, S., & Raver, M. (2023). Mapping and tracing the postdigital: Approaches and parameters of postdigital research. Postdigital Science and Education, 5, 623–642. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42438-023-00391-y

Fawns, T. (2022). An entangled pedagogy: Looking beyond the pedagogy—technology dichotomy. Postdigital Science and Education, 4, 711–728. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42438-022-00302-7

Knox, J. (2019a). Postdigital as (re)turn to the political. Postdigital Science and Education, 1, 280–282. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42438-019-00058-7

Knox, J. (2019b). What does the ‘postdigital’ mean for education? Three critical perspectives on the digital, with implications for educational research and practice. Postdigital Science and Education 1, 357–370. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42438-019-00045-y

Martin, A. D., & Kamberelis, G. (2013). Mapping not tracing: Qualitative educational research with political teeth. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 26(6), 668–679. https://doi.org/10.1080/09518398.2013.788756