Knowledge is the moat

Over the past two years, education leaders and commentators have turned themselves inside out trying to determine how we should adapt education for the age of AI. Here's why we shouldn't.

This is something I say a lot, but I’m not sure many people agree with me. Knowledge and information are not synonymous — because knowledge requires someone to know it.

Knowledge cannot exist without a knower.

AI is not a knower. It can parse information, but it cannot hold knowledge.

I suspect that these concepts feel synonymous because in ages past, information resided almost exclusively in people. The vast electronic databases and information stores we have today are pretty new. Yes, libraries have been around for millennia, but were historically tiny collections of clay tablets, animal skins, scrolls or folios. The information was preciously guarded because it was freaking labour intensive to transmit — so we really needed to make sure it was worth it. If it got old and disused, it got thrown out. Not enough space on the shelves for that.

If a book sits on a shelf, and nobody alive has read it, the information it contains is not knowledge. It was knowledge once — somebody wrote it; somebody edited it; somebody almost certainly read it once upon a time. But nobody now knows what’s inside.

Sure, perhaps we have summaries of its contents. But summaries aren’t the same as knowing: they are abridged, interpreted, and possibly erroneous. There’s only one way to know. The best knowledge claim we can make of a summary is “the author of the summary thinks this is what’s in the book”. I won’t discuss what happens to knowledge when that author is an LLM, but you get it.

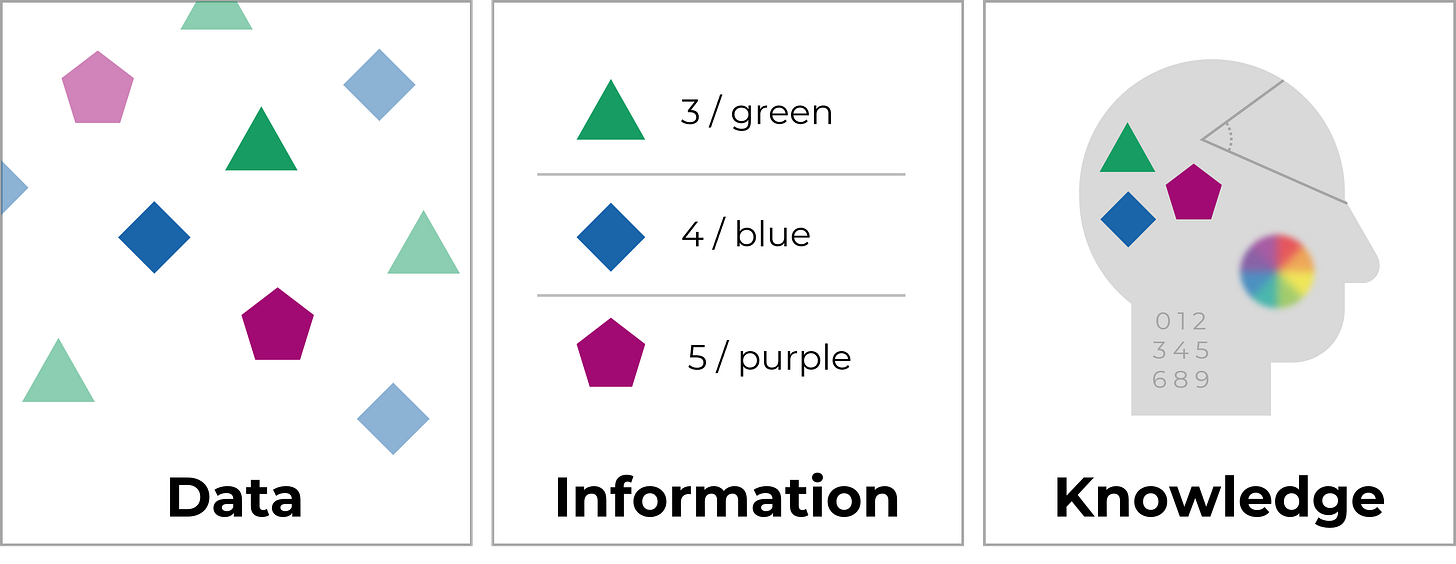

The difference between knowledge, information and data

Data, information and knowledge are critically interrelated. Each one relies on the one before it. But they are not the same. And to understand them, we need to understand their relationships to meaning, truth, belief and personhood.

Data is the raw bits of whatever that can be synthesised to make information. It has no meaning on its own — it just exists. Quantities, symbols, words, sensory inputs. A silhouette through a window pane.

Information is what data looks like when it’s been organised somehow. Some kind of sense has been made. Information can be an opinion, an equation, a graph, a news report. It has meaning, but that meaning doesn’t always represent truth. For instance, “he looks like a fool” is a piece of information, but it doesn’t mean he does. This is only my opinion. If you looked at him, you might say he looks quite snappy.

Knowledge isn’t so simple as either of these things. It’s information, but it’s true information, and someone believes it — and has a good reason to. In order to build a really strong case for belief, we use information, based on real data, well synthesised. I know he’s in there because I can see him through the window.

Like I said, it’s not simple. Is it possible to know, for sure, that anything is really true? Knowledge = justified true belief is a definition that has endured since Plato, but plenty of critiques have been levelled at this model.

For instance, Gettier asks: what if a person’s reason for believing is false, but the information itself is true? (A bad example: the person I see through the window looks like him, but is someone else. Nevertheless, he is in there, standing a few feet away.) I believe he’s in there. He is in there. But do I know he’s in there?

It’s even muckier when we acknowledge that many aspects of reality are socially constructed. That is, they are only real because we believe in them. Money, for example, is only worth anything because we (collectively) believe that it does. But it’s not a simple cogito: “I believe in fairies, therefore they exist.” It’s a more calculated, layered kind of belief: “I believe that you believe that money is worth something, therefore I can take your labour and you will accept my money in exchange”.

I hope you’ve leapt ahead to the conclusion that knowledge is dependent on personhood: a person, a sentient being, who can believe, reason, and know.

Knowledge is the moat

Tech commentators have been warning for years that GenAI has no “moat”.

Moat?

What they mean is that no AI company has an inimitable competitive advantage that separates their AI product from competitors in the market.

And yes — when it comes to AI against AI in the commercial tech market, this is true. There’s no secret sauce. Nobody has a patent on any “game changer” algorithm, which is why most of us have been waiting for China to come out with something like DeepSeek for a very long time.

But when it comes to humans against AI in the domain of learning, there’s simply no competition. Humans can hold knowledge. GenAI can only parse information. And because it doesn’t know what it’s dealing with, it frequently (up to 90% of the time) converts data into misinformation, which we erroneously call “hallucinating”.

Our students’ abilities to know, to judge, to trust and to believe are things that set them unreachably apart from GenAI algorithms. We do them a disservice by even suggesting that they should learn with AI. We’ve already seen that AI harms learning, even in the brightest and most expert of us.

I’m not advocating a ban. That’s beside the point, and unenforceable.

What I’m suggesting is that we need to honour what our students are really worth.

They’re worth so much more than this.