Where to from here: Decouple learning from qualifications

If not “secure/open” assessment, what will we do about the GenAI assessment crisis? Here, I offer the ambitious proposal that we decouple assessment-for-qualification from the relational work of education.

This proposal submits that, as argued by Corbin, Dawson and Liu, a structural change is needed to our assessment ecosystem in order to protect the validity of assessment in higher education.

Structural changes can come in many forms. For example:

Changes to the conditions in which students do their work (this is typically what we mean by “assessment security”)

Changes to the conditions in which assessors judge students’ work (such as the shift to relational assessment I have proposed earlier in this series)

Changes to the standards for quality of student work (such as converting to competency-based assessment and ungrading approaches)

Changes to how assessment judgements are used.

Currently, assessment judgements in university are quantified (that is, graded); then aggregated (multiple grades added together to produce results for whole subjects, and then averaged across whole courses to produce grade point averages); then used to issue qualifications.

It has already been established that aggregating marks in this way invalidates criteria-based judgements. As I and many others have argued, quantitative grades are already invalid, because they assign numbers to fundamentally qualitative judgements.

So how can we change the way we use assessment judgements?

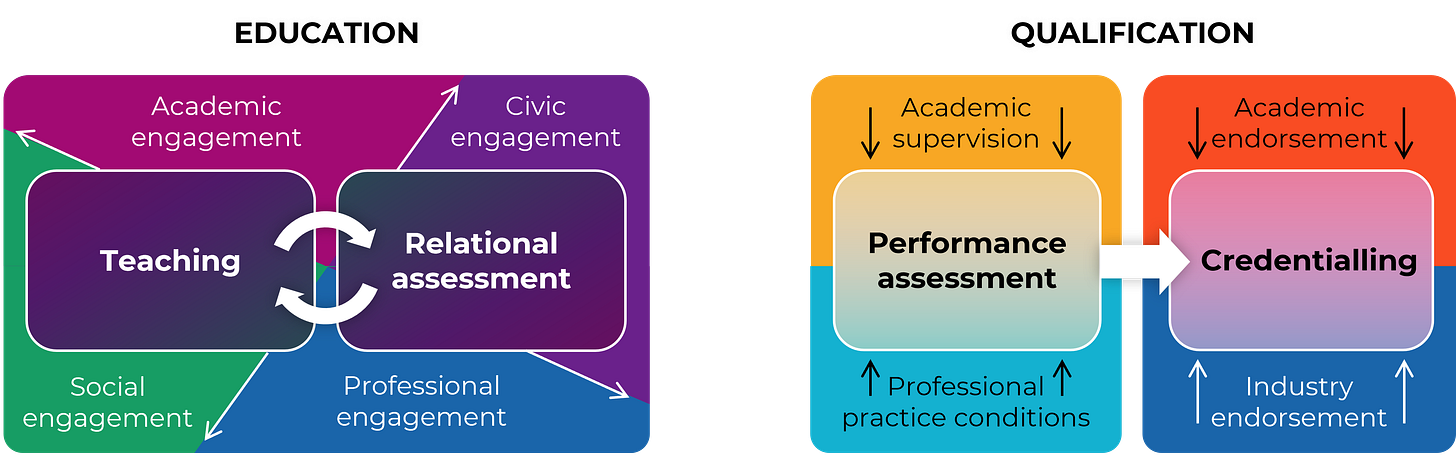

I propose that assessments for qualification be entirely separated from assessments for education. This is not a discursive distinction, like assessment for/of learning or formative/summative, but a fundamentally different process, context and outcome.

To begin, let’s define the “problem” at the heart of this crisis: cheating.

What is cheating, and why does it matter?

The answer is that there is no agreed-upon answer. I’ve previously tried to reverse-engineer a definition based on the HE regulator (TEQSA)’s framing of academic integrity. Phillip Dawson suggests that the definition of cheating is shaped and governed by the assessment security (tech) industry. Kane Murdoch suggests that cheating is about “avoiding learning”.

Of course, assessments cannot measure learning — only performance. So when we talk about “assurance of learning”, what we mean is assurance of performance. In a summative assessment, we can’t actually tell when and how they’ve learned something. What we’re really trying to see is whether they can do it.

In my view, cheating (in a game, in a competition, in a marriage) is an attempt to win without following the rules.

So in the context of assessment, we can take this to mean that the cheating student has given the appearance of correct performance, but has not done it according to our rules. No submission that hasn’t followed the rules can be used to make a valid assessment. So then the question is: what rules should we, and can we, set?

The thrust of “secure” assessment strategy within the “two-lane” and similar approaches is that if assessments are in-person, supervised, time-constrained and resource-restricted, we can enforce the rules because we’ve hardened them against cheating.

As I’ve previously argued, this isn’t strictly accurate. It’s still possible for students to bring generative AI and other deceptive technologies and strategies into the “secure lane”; it’s just more expensive.

So in order to address the problem of validity, we need to re-align our assessments — outcomes and all — with their purposes.

The purpose of qualifications

Qualifications, according to Wheelahan and Moodie, should hold several types of value:

educational value (knowledge of our world)

intrinsic value (for individual self-realisation)

use value (as a necessary foundation for an occupation)

exchange value (to access the labour market)

social value (for democratic participation and social progress).

However, Australian higher education qualifications are awarded solely based on the results of outcomes-based assessments. It is certainly not self-evident that such assessments can evidence all of the types of value above. I would argue that qualifications based on outcomes-based assessments are mostly valued for their use and exchange value: as signals of what a graduate is capable of and is permitted to do, especially in paid professional settings.

Of course, this is truer of some qualifications than others. And mostly, it is true of those qualifications that are regulated in some way by the industries they feed into: nursing, law, teaching, accounting. These are a mandatory part of a person’s permit to practice in their profession.

Some other qualifications are not mandatory, but have become proxies for capability in employers’ eyes. I’ve been a designer, a copy editor, a marketing consultant, a production manager. I’ve never had a job other than university teaching that mandatorily required me to hold a qualification, but a (general) university education has been on the list of selection criteria for every white collar role I’ve ever held.

My argument is that these kinds of qualification are different creatures. One is a regulatory licence, and the other is a general marker of cultural capital.

No employer has ever shown an interest in what I learned in university. HR departments sometimes ask for copies of academic transcripts, but they don’t actually read them, and most of my line managers have been unaware of which qualifications I held. Whether I achieved a credit or a high distinction is not information they care to know. But my experience is utterly unlike that of a student who has had to meet the requirements for legal or medical practice, whose qualifications are utterly critical to their being permitted to practice in their fields.

So, with this in mind, I propose that we separate the permission to practice from the learning and teaching of knowledge and skills. The conflation of these two things has led higher education into a global existential crisis. Fully aware that most of their degrees provide no genuine permission to practice, universities have hurled themselves upon disingenuous discourses of workforce competitive advantage.

We shouldn’t need to do this.

If learning actually matters, we shouldn’t need to do this.

The purpose of higher education

HE institutions have historically offered rich opportunities for privileged students to develop their ways of thinking and engaging with their social, civic, professional and intellectual worlds, and to build connections with others based not on geographical proximity but shared curiosity.

I know they don’t do this now.

HE, for many students, is a profoundly lonely experience. They juggle necessary paid work with scheduled classes and standardised assessment periods. Campus spaces are often corporate and clean, and students are anxious to ensure that all time and effort they exert will lead to swift returns in the form of quality employment.

But more students than ever before attend university, because a university education is positioned as necessary for quality employment, and because the government will fund their attendance.

To each according to our needs

So — what if education was restored as a space of learning, of exploration, of self and collective development? What if the business of assessing performance to issue qualifications was decoupled from this?

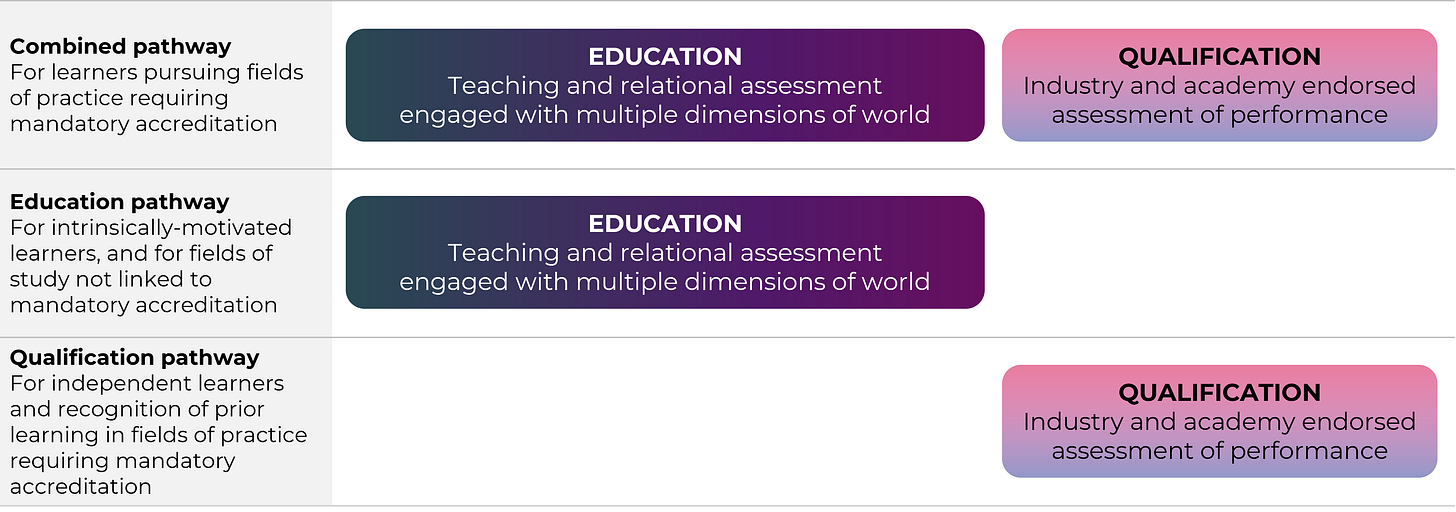

Both (education and qualification) would remain a part of publicly funded higher education. They could be undertaken together in sequence, or as individual pathways.

Assessment for education

The purpose of assessment for education would be to develop the dimensional relationship between a student, a teacher and their world. The major incentive to cheat is gone, because qualification cannot be gained through cheating, and students do not have to complete the educational pathway in order to test for a qualification.

Instead of a qualification, a student who pursued higher education in this way would build up a narrative record of their learning over the course of their studies. A little like an academic transcript, but without the Grade Point Average at the top. It would be a transparently multi-authored account of the things they tried, the things they created, the ways they developed. Failures and difficulties would be documented along with achievements — but not as poor marks that dragged down the average; rather as areas of struggle, disinterest or opportunity for growth.

Assessment for qualification

The purpose of assessment for qualification would be to verify the student’s performance under professional practice conditions and with academic oversight to ensure assessment quality. Assessment for qualification should only be done for types of professional practice that require formal accreditation for reasons of law and safety. The rules are determined not by university infrastructure but by the standards and requirements of professional practice. The development of these rules is also driven by academic principles of integrity, ethics and equity.

The incentive to “cheat” might still be present, but the conditions will be effectively identical to those in the professional world, so if students can get away with “cheating”, then so can a worker. This means responsibility for assurance of performance is shared between industry and academy. Assessments of performance will be authentic, but (somewhat ironically) not in a performative way. Instead, they will be situated assessments — that is, they will assess capabilities in the situations where they occur in practice, rather than abstracting them.

Students might choose to engage with education before seeking a qualification; or they might not. Students might choose to seek a qualification-only pathway — for instance if they had already gained the required skills through practice or independent learning. Or, indeed, students might choose to pursue education only, without a specific licence in mind. This, I might venture, is essentially what liberal arts students do now.

There are, of course, intricacies to this that need to be thought through, and I won’t attempt to do this here. Things like how to prevent people from entering the qualification-only pathway over and over again and amassing huge volumes of professional licences to practice, and how to promote the value of the education-only pathway (again, a problem which already exists in the form of ceaseless, avaricious economic pressure to defund the humanities and social sciences).

There are many details and contextual particulars that must be refined to ensure this approach can effectively address the challenges of educational and assessment integrity in current and future higher education.

But I submit that a model in which learning and qualifications are connected, but the value of each is distinct, is a model that might address a range of significant higher education quality risks including assessment validity, cheating, equity, access, equity and inclusion.

I hope this proposal is coherent, though it is incomplete and tentative. I am eager for your perspectives, ideas and critiques, to pressure test, correct and improve on our collective vision of higher education assessment.

References

Baron, P., & McCormack, S. (2024). Employable me: Australian higher education and the employability agenda. Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management, 46(3), 257–273. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360080X.2024.2344133

Biesta, G. (2021). World-Centred Education: A View for the Present. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003098331

Corbin, T., Dawson, P., & Liu, D. (2025). Talk is cheap: why structural assessment changes are needed for a time of GenAI. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2025.2503964

Dawson, P. (2020). Defending Assessment Security in a Digital World: Preventing E-Cheating and Supporting Academic Integrity in Higher Education. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429324178

Dawson, P., Bearman, M., Dollinger, M., & Boud, D. (2024). Validity matters more than cheating, Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 49(7), 1005-1016. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2024.2386662

Dutriaux, L., Clark, N. E., Papies, E. K., Scheepers, C., & Barsalou, L. W. (2023). The Situated Assessment Method (SAM2): Establishing individual differences in habitual behavior. PLoS ONE, 18(6), e0286954. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0286954

Fawns, T., Bearman, M., Dawson, P., Nieminen, J. H., Ashford-Rowe, K., Willey, K., Jenson, L. X., Damşa, C., & Press, N. (2024). Authentic assessment: from panacea to criticality. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 50(3), 396–408. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2024.2404634

Murdoch, K. (2025, June). I find “cheating” a slightly silly concept- I prefer “avoiding learning”- but the adults in the room need to stop projecting [Post]. LinkedIn. https://www.linkedin.com/posts/activity-7343554265367441408-hv35/

Reynoldson, M. (2025, July). Where to from here: Foster educational relationships. The Mind File. https://miriamreynoldson.com/2025/07/01/where-to-from-here-relationships/

Reynoldson, M. (2025, July). Where to from here: Revise assessment standards. The Mind File. https://miriamreynoldson.com/2025/07/01/where-to-from-here-revise-standards/

Reynoldson, M. (2025, June). The off ramp: tests, trials, and the myth of meritocracy. The Mind File. https://miriamreynoldson.com/2025/06/26/the-off-ramp-meritocracy/

Reynoldson, M. (2025, March). Academic integrity – a dishonest term? The Mind File. https://miriamreynoldson.com/2025/02/21/academic-integrity-is-a-dishonest/

Reynoldson, M. (2024, July). Affective and agentic spaces in the postdigital university.The Mind File. https://miriamreynoldson.com/2024/07/05/affective-and-agentic-postdigital-university/

Sadler, R. (2010). Interpretations of criteria‐based assessment and grading in higher education. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 30(2), 175–194. https://doi.org/10.1080/0260293042000264262

Wheelahan, L. & Moodie, G. (2025). Revisiting credentialism – why qualifications matter: a theoretical exploration. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/01425692.2025.2529814