Permanent liminality, transitions, and "being both"

Dwelling in the discomfort of lifelong learning

This is a contemplation on liminality in the chaos of late modernity. As I wrote it I was thinking about “lifelong learning”, but I think the point is it applies to just about everything in adult life now. I’d love your own thoughts on what permanent liminality looks like in your own life.

In today’s climate of constant development and change, we are all obligated to maintain a tireless orientation to learning. It is unacceptable now to complete one’s schooling at 18, dust off one’s hands, and say “well—that’s me learned, then”. Tomorrow something is going to happen that chips away at the relevance of your schooling. You’ll need to patch it up. You need to keep the mortar wet. You need to accept that one day you might have to full-on renovate.

So, we are all—like it or not—lifelong learners. We google weird things people say to us. We gobble PD at work. We seek the company of people whose knowledge we might borrow. If we have the resources and the patience, we enrol in courses.

But learning is uncomfortable. A fair amount of the time, we choose to refuse it. For all the things I googled, think of the things I didn’t. For all the people I meet who know things I don’t know, how many do I actually choose to listen to? It’s exhausting—and it’s also threatening. Being wrong sucks. Every time I notice there’s something I don’t understand, it makes me feel less sure of what I’m about. So learning is a selective task.

Various writers have linked the processes of learning with the concept of liminality. This is an alluring, rather mystical term that emerged from anthropological studies of rites of passage1: those rituals and ceremonies that mark the transition of a young person from one status to another (from layperson to cleric, say, or from girl to woman) within a culture. The word limen refers to the figurative threshold crossed within such rites; the space and the moment of transition.

Liminality, too, is uncomfortable. The acts performed in these rituals can be confronting, painful, humbling. People are watching, and the person going through them is kept separate from the crowd.

“Liminal entities, such as neophytes in initiation or puberty rites, may be represented as possessing nothing. They may be disguised as monsters, wear only a strip of clothing, or even go naked, to demonstrate that as liminal beings they have no status, property, insignia, secular clothing indicating rank or role, position in a kinship system - in short, nothing that may distinguish them from their fellow neophytes or initiands. Their behavior is normally passive or humble; they must obey their instructors implicitly, and accept arbitrary punishment without complaint. It is as though they are being reduced or ground down to a uniform condition to be fashioned anew and endowed with additional powers to enable them to cope with their new station in life.”

Victor Turner

Fun! But the discomfort is part of what makes the ritual so powerful: there is a cost to valued change. The neophyte submits because the transformation is worth it.

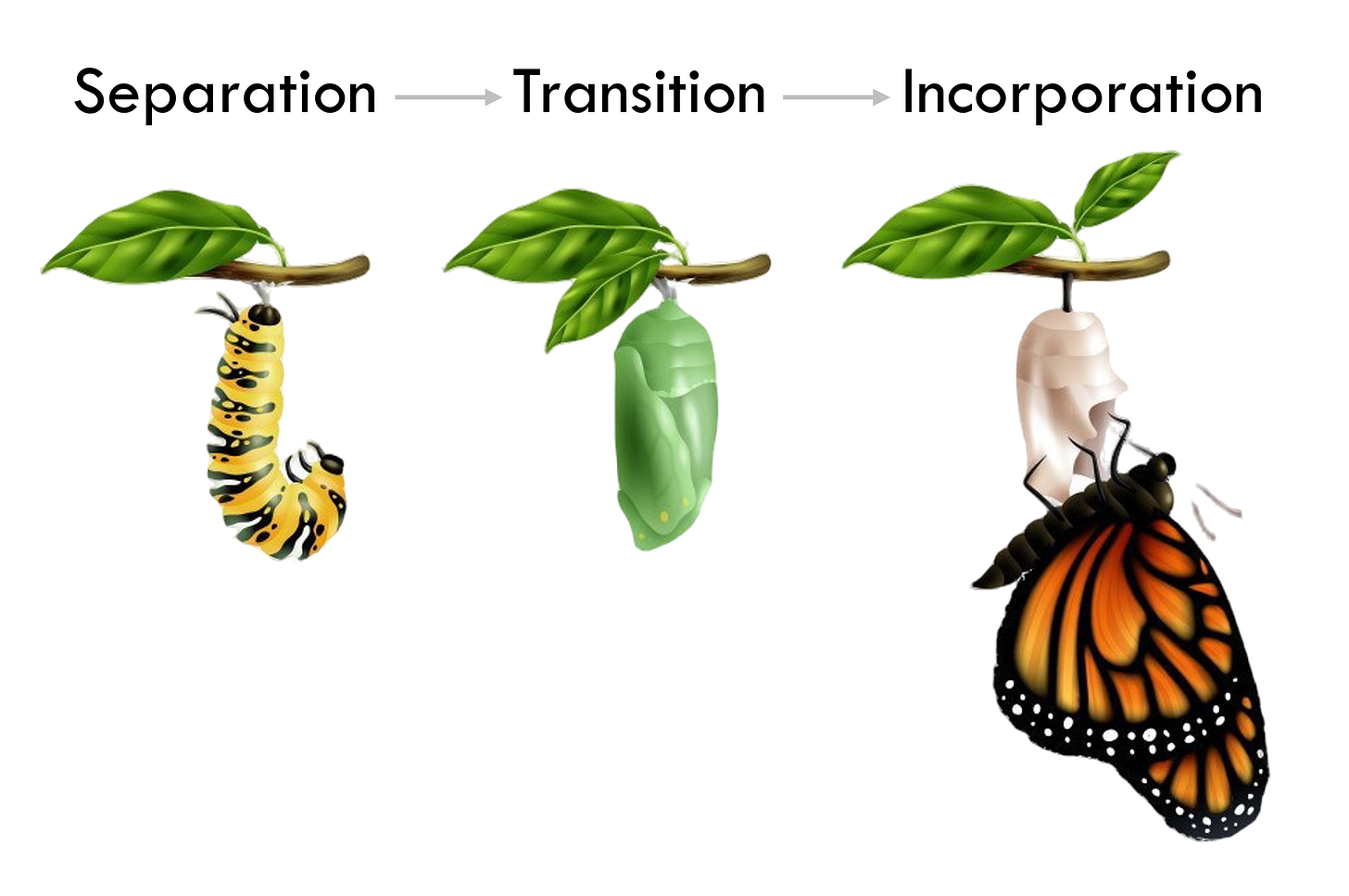

An enduring symbol in nature is, of course, the transition of the caterpillar, whose larval body must be completely dissolved in order to re-form as a resplendent (if short-lived) butterfly.

Turner’s2 original construct of liminality came with conditions. The anthropology-derived model sets the criteria that liminality is temporary, obligatory, guided by others, with cultural legitimacy and pre-determined outcomes.3 The caterpillar has no choice but to transform, and can only transform into a butterfly. (Or one of these fellas.) It’s all very organised and proper.

Learning in school and university is akin to these kinds of rites. For a culturally-determined period of time, the kids are holed up in special locations (The Classroom, The Lecture Hall) to be shaped and guided towards the knowledge society requires of them. They are humbled, disciplined, kept separate. They must also submit to a sequence of painful trials (NAPLAN, term papers, group presentations) through which they must successfully pass in order to emerge as fully-fledged members of educated society.

All critique aside, it’s a Big Deal because it’s worth it.

But… what does liminality do to us as lifelong learners? We (willingly or begrudgingly) resubmit ourselves for the threshold. But as adult life cartwheels chaotically on, we hardly have the time or space to climb into a chrysalis and dissolve. So lifelong learning tends to happen without ceremony: surreptitious googling, study blocks in the small hours, graduating in absentia on a work day. Sometimes we have guidance, and sometimes we have only ourselves.

Liminality looks different in lifelong learning. We have to occupy a kind of superposition, both the before and the after—and sometimes, quietly, the in-between. We are (to inappropriately steal a phrase from Turner) “threshold people”. It’s awkward, and it doesn’t end—it can’t. The moment we stop learning, we begin to lose our place in the world. So what does this new kind of liminality actually look like?

What do we need to make it a livable habitat for always?

Van Gennep, A. (1909). Les rites de passage. Émile Nourry.

Turner, V. (1969). The Ritual Process: Structure and Anti-Structure. Aldine Publishing.

Ibarra, H., & Obodaru, O. (2016). Betwixt and between identities: Liminal experience in contemporary careers. Research in Organizational Behavior, 36, 47-64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.riob.2016.11.003