I’ve noticed a fair bit of commentary lately about adjustments and accommodations for university students with special1 needs. There have been a couple of recent high profile articles2 arguing that if students need adjustments to perform well, then they’re not actually very good performers and their degrees aren’t worth as much.

Which… I don’t need to say it, but ew.

There are many extremely good arguments against this rhetoric, in defense of accommodations, widening access and supporting educational flexibility, and I don’t think I need to repeat them. I think what actually needs to be examined at this point is what drives people to argue against educational inclusion in the first place.

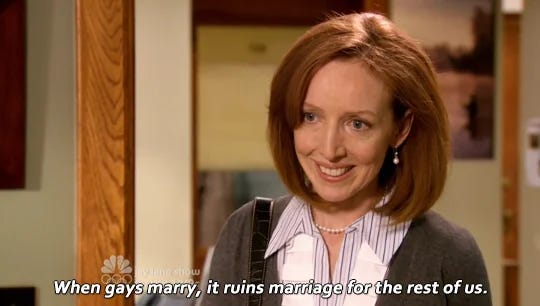

It’s hard not to think of this.

I mean, I get it. I was a huge nerd at school (NO!) and my academic abilities were precious to me. They gave me something to be proud of when I struggled socially, lived with undiagnosed depression, felt like an outcast wearing K-Mart clothes while the kids around me were rocking Pumpkin Patch. (I grew up in a fancy suburb but my family was not fancy.)

I suspect the commentators that make these kinds of statements championing academic elitism probably have a similar relationship with their own high intellects (or wealth, or social status): such traits are, fundamentally, a treasured part of one’s identity. I mean, look at this:

But if someone else who didn’t appear to have those traits before is able to put them on like a hat (provided that hat is adjusted to fit), then were we wrong all along about our own identities?

The protective response is, of course, to argue that it’s not the same hat, because they had to change it to put it on. Sure, we both got first class honours, but yours doesn’t count for as much as mine because they gave you extra time in the exam.

I’m not sure there’s a solution. The reality of being human is that each of us has some core urges to stand out from the pack (insert some cod-evolutionary psychology about attracting healthy mates). But if everyone’s special, no one is.

Is that right, though? Does someone else’s specialness make our specialness less special? Especially if theirs is a different kind from ours? It seems to me that a part of what’s behind this is quantitative thinking. That is: the desire to weight each characteristic of s person in a way that makes it possible to aggregate and rank people against one another. Indulge me a moment (if we were in a coffee shop, this one would go on a napkin):

If you think about people as diverse and qualitatively different from one another, you can describe them, but it feels kind of nebulous and subjective and irreducibly complex. If you think of their differences as quantifiable (for argument’s sake, say brains are “worth” more than brawn) then it’s possible to rank them in a comforting little line. Some people are special, and others are just “special”.3

Everyone knows what the air quotes mean.

When poor people go to university, when disabled people have successful careers, when gays get married, it has the effect of revealing that air-quote distinction as imaginary. Turned out we were all just people.

I’m not saying that going to university, career success or marriage aren’t special. They are — if they’re what you want. But no matter how many centuries of work we do in championing equity and human rights, we still all have a deep down primal urge to one-up each other. It doesn’t go away.

I don’t actually think it is about prejudice, or classism, or bias (though it absolutely fuels those things). It’s deeper and far less specific than that. We just want people to know we and our babies are superior.

Education leaders have a moral duty to be better than this. We’re at this inflection point when the demographics of higher education are irreversibly changing, growing, diversifying (see Trow, Cantwell, Marginson, etc.), but the academy has a centuries-old heritage of elitist thinking that falsely equates academic success with human worth, and ranks its pupils accordingly.

That needs to go.

Note to my father only: don’t say it. Don’t.

These two articles require accounts to access, but for reference, a couple of recent opinion pieces were penned by Justin Noia of Providence College and David Butterfield, formerly of the University of Cambridge.

There you go Dad.